Checking In Vol. 4

Links, tunes, and a little of the new novel.

Greetings, all. It’s just after Independence Day here in the US, and it sure feels like whatever country makes it to the next won’t be this one. For now, some links, some songs, and another snippet of the novel.

Links

I went Hobermode for Mubi, writing about cops, robbers, army vets, white supremacists, and the American dream:

The Rambo narrative rhymed with another peddled by some returning veterans. According to these thousands of soldiers, writes the historian Kathleen Belew, “The corrupt government sent American boys to Vietnam and then denied them permission to win by limiting their use of force against a beastly, subhuman enemy.” Like the proto-fascist reactionaries of Weimar Germany (and like Rambo himself), these veterans believed that they had been “stabbed in the back” by cowardly bureaucrats and disloyal civilians. Some of them would go abroad as mercenaries, to command death squads in Central America and prop up the apartheid regime in Rhodesia. But many others, Marines and Green Berets and regular grunts, stayed in the United States to organize, train, and arm the white-power movement. They would continue at home the war they had lost abroad.

For Liberties, I dug into the Trump administration’s sadistic propaganda campaign, and what it reveals about the country’s fraying social fabric:

Americans seem to have an enormous appetite for these spectacles of violence and degradation, so long as they are perpetrated against people outside the protection of the law: terrorists, gang members, sex offenders — or anyone this administration decides to treat that way. Whole classes of online entrepreneurs, from the private individuals who ‘investigate’ human trafficking and the ‘pedophile hunters’ who take the law into their own hands, have successfully converted law enforcement into entertainment, democratizing the process that began on reality TV by extending it to cover the entire country, the whole world.

At the Atlantic, I reviewed Pip Adam’s sublime new novel in the context of competing strains of science-fiction:

Like the billionaires and their sci-fi dream weavers, Adam is using outer space to imagine alternative forms of human relation. But with Audition, she wants to escape the gravitational trap of Earth’s prejudices and hierarchies, its forms of ownership and exploitation. Rather than making space a lockup for the unworthy, or a new frontier upon which to exert our will, she searches for something far more expansive among the stars. We must move, she suggests, beyond the hard borders that separate, isolate, and constrain life on Earth today. Across the event horizon lies true possibility. But first we must find our way out of the cage.

I reviewed Martin Niedekker’s delightful, mind-expanding Strange and Perfect Account From the Permafrost, for the Washington Post:

Rather than the isolated individual of the modern novel, Niedekker is searching for a non-dualist perspective in which there is no real separation between the “one” of the narrator and the “all” of the world. His poet is both a long-dead Dutchman and a conduit for an array of individual and collective experiences, a fluid perspective that ranges widely without ever losing the chatty, chummy touch of its central voice. If the narrator occasionally goes on a bit too long about his fairly dull career as a young poet, we forgive him when he shares the story of the polar bear that, after exploring the cabin where the poet and his crew attempted to survive the winter, walked away with an ink pot. “What does the smell of dried ink make a polar bear think of?” he wonders — a roasted animal, a winter den, human danger, the bear’s own childhood? Niedekker wants to expand our expectations for the novel and in the process what we expect of ourselves; to make us consider how the history of mankind might overlap with “the history of islands or the history of the snowy owl,” and how our own violent history — of knowledge as a spur to and by-product of conquest — has so often disrupted other histories.

I analyzed Wes Anderson’s spiritual turn, for Commonweal:

He has equipped himself to survive assassination attempts and international industrial sabotage. He is much less prepared to deal with his daughter Liesl (Mia Threapleton), a pious young nun in formation who wants nothing to do with the empire she will inherit. And then there are Korda’s visions of the afterlife, a black-and-white stage set full of fluffy clouds and robed personages and the figure of Liesl during the years when he abandoned her. He has the first of these visions after the opening assassination attempt, and they pop up throughout the film, rupturing the pastel-colored hijinks with their visions of death, abandonment, and celestial justice. These visions of a world to come are in keeping with Liesl’s beliefs, and yet it is Korda, an atheist, who receives them, and only he can transform their ambiguous meaning into actions.

Songs

John K Samson - Provincial

An upcoming article brought me back to Samson’s first solo album, and while I can’t honestly say it’s my favorite of his albums (Left and Leaving forever and ever) it has always struck me as the most resoundingly human. I particularly love this one, with its spare economy of suffering and surrender. “I practice my English on nurses, 'Oh, that's a nice name.' / And they may ask for mine, but the burns on my back from the x-rays / Say I shouldn't show anyone anything ever again.”

Idlewild - The Remote Part

A little more than ten years ago I took a trip through the Scottish Highlands and islands by train and boat and bus and a couple desperate hitchhiking attempts. I had known Idlewild for awhile, since I found a copy of 1001 Broken Windows at my college radio station, and before I left I picked up a selection of Edwin Morgan’s poems from Galway’s great Charlie Byrnes. I think the one discovery precipitated the other, though I can’t honestly say. More fiction, perhaps. I always gravitated to this song, I don’t really know why. Idlewild have put out other albums since The Remote Part, and have a new one coming this summer. But they’ve never quite topped it.

One more from the summer of 2015. I have a distinct memory of rolling into Chisinau on the overnight bus with this song blasting in my headphones. Hard to imagine why an account of the apocalypse might resonate today.

Godspeed You! Black Emperor - "NO TITLE AS OF 13 FEBRUARY 2024 28,340 DEAD"

Caught thee mighty Godspeed at Pioneer Works at the tail end of New York’s deadly heatwave. We’re in this together. Hail hail hail.

A Snippet

Since the end of last year I have been writing a novel I am calling The Searchers. A few months ago I shared an excerpt from the beginning of the novel, and now I wanted to share something from Chapter 4. It’s rough, and hasn’t really been revised, but I wanted to show you all the same. Enjoy:

The ferry docked in the middle of the afternoon, and we bought four seats in a minibus heading for villages around Valbonë. Once we managed to explain what three Britons and an American were doing in the Albanian Alps, the driver dropped us at a simple wooden guesthouse run by a fifty-something woman whose family had emigrated to the Bronx. None of us had thought to pack food for the trip, and we arrived at Rovena’s lightheaded from hunger. She seated us on the patio beside a group of middle-aged men, officials from the education ministry on their way back from a conference in Pristina. Was Kosovo really so close? Oh yes, yes, they assured us, closer even than London! “A bit of humor,” the youngest clarified, and invited us to share their lunch.

The men ordered for us, suggested the order in which each dish should be consumed, and even instructed us on the best way to enjoy Rovena’s raki which, they all agreed was quite good, the very best. It tasted like rubbing alcohol, and you had to wash away the flavor with a sip of water and a forkful of cottage cheese. Around the third course it began to rain, and rained on through the night, and when we met in the lobby on the following morning the whole of the valley had filled up with clouds. Rovena advised us against hiking until the fog lifted; it was no good on the mountain, she said, we would lose our way, and even if we somehow didn’t, the whole day would be spent wandering the murk, and we would see nothing on our way over to Theth. It would be better for us to stay a second night, or perhaps even a third, and besides, there was so much that we had not yet seen in Valbonë—she could even recommend a guide.

Her talk swayed Cor, who swayed Mark, who began to sway me. Only Anna dug in her heels, and would not listen. “I’ve not come all this way to skulk around,” she insisted, “to waste time indoors and shill out for another night, all over a bit of fog. We came here to hike, so let’s hike.” She tightened the straps on her pack. “Join me or not, but I’m going.” And she left us behind, and headed out into the fog.

The day before we had arrived in a wide valley thick with trees from wall to wall. Peering up the valley towards those soaring peaks, I could not imagine how we would find a passage to the next valley across that ridge. Yet it seemed so much more impossible now. By the time we caught up with Anna the landscape around us had dissolved, leaving only a milk-white residue where from time to time a house, a tree, a corral might emerge, and then melt away again. She was furious at our desertion, and would not slow her pace, not even to acknowledge us. No, she pushed on forward along that stone road which curved through the seasonal streambed, past the last guesthouses, the small unnamed villages marked off by their fence pickets, the marked-off pastures and stone-walled barns with their fallen-in roofs—on and on, marching silent and intent as the ground rose and the trees thinned and we left the last of that human landscape behind.

Even after climbing steeply upslope for the better part of two hours, we had yet to clear the fog. None of us had brought a map; we had been told the path would be easy to follow, and for a good while it was, until we looked up in our way across a clearing and found a stone trough and a water pipe, but no trail before or behind us, only the meadow, the pines, and the mist. I don’t think it had occurred to anyone that Anna might have been leading us astray, and until that moment I very much doubt it had occurred to her. She reached the well, spun around, spun back, took a few steps forward before retracing her steps almost exactly to pass us on the way back downhill. Yet even the gap in the trees through which we had just passed seemed to have closed up behind us now. I see us now like the chasseur in that painting by Friedrich, trudging blindly through the dark and menacing woods—though the image could hardly have come to me at the time, ignorant ass that I was and remain. Perhaps it came to cultured Anna as she traced the clearing, mucking her boots and soaking her socks as she searched for some way out or back. She did not apologize or attempt to excuse herself, and she did look up to ask for our help. No, her eyes were fixated furiously on finding some exit from this blind impasse into which she had blundered, and the rest of us had followed. So we sat on the dry edge of the trough, and waited.

Anna was busy peering into the brush near where we thought we had entered, when she paused and turned one ear to the woods. She had heard something, and soon we heard it too, a bright high bleating followed by a man’s hoarse voice, then the bleating and again the man, and like in those magic stories told to soothe children, the impenetrable wall of the forest parted, and a donkey loaded down with heavy plastic sacks sauntered into the clearing, with a man close behind. Both seemed equally puzzled by our presence there, these bewildered foreigners in waterproof boots speaking in their various unintelligible languages. The man drove his donkey towards the water, and only when Anna called out: “Are you coming from Theth? Theth? Theth?” did he shake his head and wave his stick the way he had come and reply: “Po, po, Theth,” pronouncing the name as none of us could have imagined, and signaling Yes with that motion which everywhere else in the world means No.

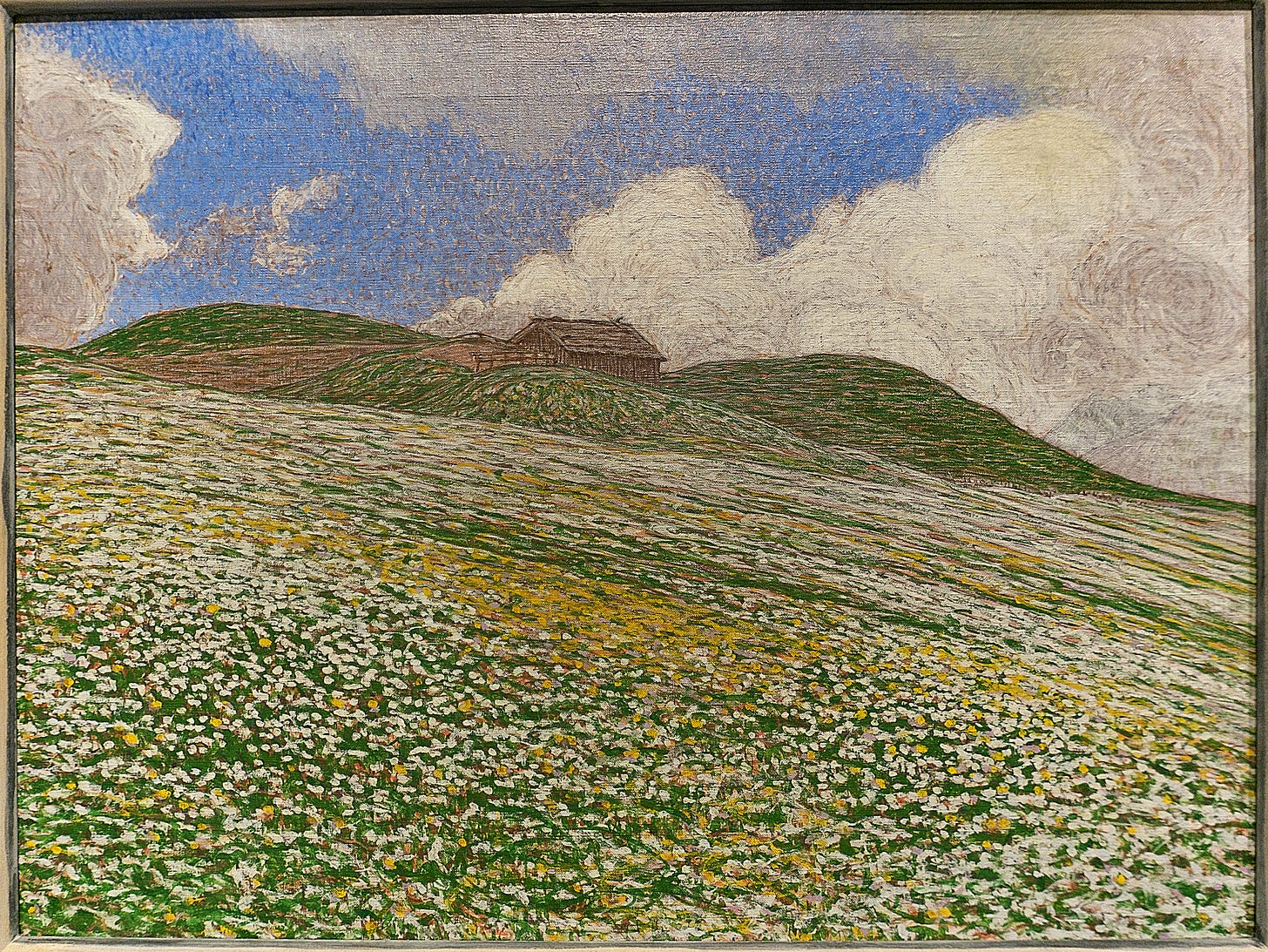

The path was in fact just on the other side of the trees, marked clearly by a sign all of us had missed for the fog. Within another hour we had switchbacked high up the ridge, until at last we rose free of the clouds, and onto the pass. The valley behind us was still a bowl of stagnant water, a gray and brackish mixture cupped between tall peaks. Yet laid out before us was a great green resplendent landscape without even a single cloud to mar the view. “See?” said Anna through her faltering smile. “Told you I’d figure it out.”

—Til next time.