Checking In Vol. 7

Links, songs, and various recommendations.

Léon Spilliaert — October Evening, 1912

Greetings all. It’s dark now, it’s cold now, Fall came late and slipped out after about three weeks. As the great sage Tim Robinson tells us: what the hell.

Still, it’s been a big one for me. I published, I traveled, after a long break I got back to the novel. So buckle in: this newsletter is a big boy.

Links

First, my very long, very long in the works—just checked: I wrote my first draft over the summer of 2023—essay on the master, Yasunari Kawabata, and my own personal history with Japanese literature, was published in the Fall 2025 issue of Liberties:

In 2017, I took my copy of Snow Country from Melbourne to Tokyo. I read it quickly, incompletely. I remember feeling at a loss, held apart from the characters, both thrilled and disoriented by the conclusion. So over the next few weeks I found copies of A Thousand Cranes and The Master of Go, as well as books by Mishima and Endo, and I devoured them as I went. I read them in Nikko, across the mountains from the Yuzawa snow country. I read them in Kyoto, in a coffee shop in Arashiyama. And I read them in Kamakura, where, on April 16, 1972, Kawabata went to an apartment in Hayama and drew a bath. He unhooked the gas line — on purpose? by accident? — and died.

When I think back on that time, I remember being shocked by the suddenness of Kawabata’s revelations: the roaring milky way, the broken tea bowl. I was young, I was in a foreign country, I was open to everything, like a house with all the windows flung wide. I took it all in, and reflected later. Several weeks later I came to Tsuwano, in the mountains west of Hiroshima. One night, I was eating a simple sushi meal by myself when a pair of men approached me. They were English teachers and were celebrating a colleague who was changing schools. Would I like to join them?

I spent that night with perhaps twelve other teachers, and after many drinks they asked what I was reading, and I told them. They didn’t think much of Endo, Mishima was too patriotic, Kawabata far too old-fashioned. A middle-aged man from Izumo described him as a “classic” whom few people actually read. He wrote his email on a piece of paper and told me to write him. I folded the slip, put it in my pocket, and lost it on the way back to my room.

Liberties also asked me to submit a dispatch from this year’s New York Film Festival:

Nuestra Tierra screened at NYFF under the title Landmarks, but I prefer the literal translation: Our Land. For as Martel carefully, humanely unspools, the community and the people of Chuschagasta very much exist. The Amíns of the world may have their deed and title, but as one woman memorably remarks: “Paper does not question the pen.” Those in a place to establish the law are also the people in charge of its interpretation and enforcement, creating a series of escalating distortions that spiral throughout Argentine history. Martel frontloads her film with legal and historical evidence only to devastatingly pick it apart, allowing her many indigenous interlocutors to highlight what that evidence leaves out, and to submit evidence of their own. Their memories, their photographs, their common histories and family names: all attest to a continuity of communal life that predates and survives the traumas of colonization, independence, and legal dispossession.

I wrote another for Commonweal, covering the festival’s many movies-about-movies, and the work of an artistic life:

Ditto Noah Baumbach, who seems determined to extend his cold streak with the help of multiple movie stars and all the picturesque locations Netflix’s Oscar budget can buy. His latest effort could be worse—we’re not talking about another White Noise here—but few films in recent time have evaporated so immediately from my mind as Jay Kelly, a pleasant, sentimental, and grossly oversold rehash of clichés about aging movie stars. George Clooney does his best as the title character, a leading man of a certain age who might be a good stand-in for Clooney himself if Clooney had spent his late career starring in special-effects blockbusters rather than hawking coffee and tequila. Despite what some other characters in the film tell us tell us, Kelly isn’t an especially bad guy. Nor is a particularly great actor. He’s just a pro, a man who has prioritized his professional accomplishments at the expense of most other things in his life: his marriages; his relationships with his daughters; and his friendship with Ron (Adam Sandler), his devoted manager and ostensible friend.

It would be pointless to detail the plot of Jay Kelly. Very little happens in the film that could not have happened differently to the same effect with the same evergreen themes. Suffice it to say that, on a whim, Jay jets off to Tuscany to receive a career-achievement award and to reflect, via glossy flashbacks, on important moments in his young life—an act of reflective self-mythologizing that the film encourages us to transpose onto Clooney himself. Jay Kelly even ends with an in-film montage of the real-life star’s greatest hits, a rousing deployment of middlebrow film clips that unites everyone in Jay’s life in a celebration of, well, George Clooney.

Commonweal also published my review of one of the Festival’s true low-lights:

After the Hunt presents itself as a film of ideas, but its references to philosophy—Adorno, Agamben, the panopticon—never advance past Introduction To. Rather than digging into the genuine human complications turned up by any rigorous exploration of perspective, it presents a series of simple inversions. Would you believe that a student can have more power than her professor? That a Black woman can be rich and a white man poor? Take that, libs! Hank and Maggie both justify their behavior with references to different ethical theories, but in each case this comes off as mere rationalization. Both people, we are meant to conclude, are self-satisfied and self-seeking. The ideas are just a fig leaf.

Thankfully, the good people at Defector let me write about one of the best, with a bit about the defiant preoccupations of American maestra Kelly Reichardt:

Still, there is an expansiveness and a drive to The Mastermind that is genuinely new in her work. Few would describe Kelly Reichardt as an action filmmaker, but I’m about to. Her films are fundamentally about watching people work, extrapolating who they are from what they do. Her eco-thriller Night Moves manages to make the lo-fi labor of blowing up a dam (buying a motorboat, building a fertilizer bomb, skulking around in the dark) into high-tension stuff, without music or fireworks. She has a Bressonian affection for hands and the work they do. In her films, even an act of impulsive violence is depicted with careful observation.

So it matters to the Reichardt project that J.B. Mooney is not working. His alienation is both physical and spiritual, the frustrated ennui of a man who longs for an outlet and comes up empty. Perhaps he stole the paintings to sell, perhaps to squirrel them away. Perhaps he concocted the entire plan just to give his life a shape. He seems infinitely more comfortable when stashing away the stolen goods than he does relating to his kids or pleading with his wife. Swaddled in the loving embrace of family and suburbia, he acts like a man living hand-to-mouth, creating new problems so that he—and the women in his life—can solve them. Like a cornered animal, he must do something, or die. It’s not so much a high-wire act as a slow ascent up a shaky ladder with no way to climb back down. As someone tells him once the scheme has already fallen apart: “I don’t think you thought this one through.”

I reviewed the new Jon Fosse, and wrote a bit about his spiritual simultaneity, for the Washington Post:

In his Nobel Prize lecture, Fosse spoke of a “silent language” that serves him as a guide, directing him by intuition rather than intention. At his best, this generates a sensation of existential contingency in the reader, a quality of chance at odds with the fixed linguistic content of a novel. “Vaim” floats between states, intermingling life and death, present and past, an interstitial novel about lives that never quite arrive at their culmination. When Jatgeir attempts to express this, the result is incomplete, full of pauses and retractions: “In a way reality has probably always been, yes, no, no not like a dream, but reality has had something dreamlike about it too probably my whole life, reality is in the dream the way the boat is in the water, I think.” Not exactly poetic, but this vision of a life spent bobbing between the fixed and the dreamlike neatly describes Fosse’s oeuvre, where language gestures beyond itself and life speaks, sometimes, in silence.

Finally, a piece I’m quite proud of. The Baffler asked me to review a new collection of essays by Jenny Erpenbeck, which transformed into this much more expansive hybrid essay on the meaning and significance of ruination and the ruined. Check it out:

When a world dies, much dies alongside it. Ways of thinking, ways of building, ways of living so mundane no one noticed their presence or their passing. “Whenever a thing disappears from everyday life,” Erpenbeck writes, “much more has disappeared than the thing itself.” The evaporation of the DDR shifted border lines, political formations, rights of free trade and free passage. It allowed former East Germans to replace damaged tights, to fill their apartments with brand-new furniture, to bring back espresso machines from their trips to Italy, just as it allowed them to get rid of their darning thread, to junk old wooden furnishings, to get rid of those coffee pots that Erpenbeck remembers on the table of her family reunions, always pear-shaped and full of weak coffee and always with a foam rubber roll around the lid to catch stray droplets.

Overnight, East Berlin became Berlin, and East Germans became Germans, though the landmarks around them remained the same. Erpenbeck’s Berlin was still pockmarked with ruin, with the open spaces left by the bombs of the last war. Her Berlin was a city of vast sunsets and bare fire walls, of “barren sites, often on street corners, where nothing grew, not even a kiosk”—of places which, because they had become abandoned, were repurposed by citizens just like herself, a public-private project that remade the city in the image of its most adventurous residents.

A common ruin is definitionally idle. You cannot live in it, cannot make it turn a profit; and it produces nothing but further ruination. Urban real estate is only physically immovable; its abstract value now extends to meet the sky. With the reunification, all that space became property, and its function had changed, because the governing logic of reality had changed. Waste ground could not remain waste; the reminders of the last war must do something more than simply remind. So the Deutscher Dom was rebuilt; the Museumsinsel restored; the empty spaces were cleared by bulldozers, and new buildings in a faux-classical style filled them. Things That Disappear provides us with a record of such alterations. The shared spaces between apartment buildings are dissected and fenced off, until they become unusable/impassable. Erpenbeck’s son’s nursery school in historic Mitte is sold off and demolished, more valuable for its property than whatever educational purpose it might have served. Even the Splitterbrötchen pastries she grew up eating are now scarce. It is her own world which has become the relic, the curio, the tumbledown ruin. Or perhaps a skeleton, “individual bones with a great deal of soil in between.”

Henry Lintott — Avatar, 1916

Songs

Red River Dialect — Basic Country Mustard

I’ve been listening to David and friends for more than a decade now, and RRD’s landmark Tender Gold and Gentle Blue soundtracked some seriously formative years. He’s put out some very good music since (check out his deeply monastic solo debut), but Basic Country Mustard, out this Friday, is the best album, front-to-back, that he’s made in a long time. It’s tender, intense, whimsical, searching, and very worth your time.

Anna Von Hausswolff — Iconoclasts

I’ve always tried with Von Hauswolff, but never quite clicked—until now. Iconoclasts rules, flat-out. There are moments that remind me of Tim Hecker and Siouxsie and Bowie’s Berlin trilogy, and then you have stuff like “Unconditional Love” which just lifts off into outer space and never comes down.

Big Thief — “Grandmother”

Big Thief come in for a lot of ill talk but they remain the most talented musicians I have ever seen live, and this Fallon performance captures it all. I liked the song quite a bit on record but this version feels like it could go forever and never exhaust itself. So many little moments: the cuts to Laraaji, the back-up singers bouncing on the balls of their feet, how Adrianne seizes up in moments of extreme tension, and then liquifies without losing the beat. Missed them on this tour, but I won’t on the next.

Chat Pile and Hayden Pedigo — In the Earth Again

Dreamy, dreary, deeply saddened. Not sure I expected Chat Pile to go soft or Pedigo to get hard, much less that together they would basically make an industrial shoegaze record, but I’m very glad everybody did their thing.

Rosalía — Lux

You don’t need me to tell you, or perhaps you do. Some will and should roll their eyes at the whole “she sings in 13 languages” thing but unlike any of her contemporaries Rosalía has the voice to pull it off, and the vision [ugh] to make sure “Hildegard van Bingen pop album” ends up as something significantly more than a joke.

Neil Young — Cortez the Killer (Live at Budokan)

Happy 80th, Neil. Too much to say about this one, so here’s one quick observation: this 1978 live take contains the platonic ideal of guitar tone.

Thomas Cooper Gotch – The Lantern Parade, 1918

Recommendations

My friend Matt Spencer is a fantastic translator and a truly great hang, and for the past few years he’s run the excellent small press Paradise Editions from the outskirts of Philly. Last months he translated four short essays by Heinrich Von Kleist, and published them in a beautiful hand-bound pamphlet. Seriously, look at this bad boy:

Buy a physical copy here, or a digital copy for a mere $2.50 if that’s your thing.

Speaking of talented friends. Last month, Unnamed Press put out my good friend Laura Venita Green’s awesome debut Sister Creatures. I first read bits of this book all the way back at the start of my grad program, in that final fabled Fall before Covid broke the world and inspired Ari Aster, and it remains as seriously strange and deeply, defiantly weird as I had hoped way back when. Great cover too:

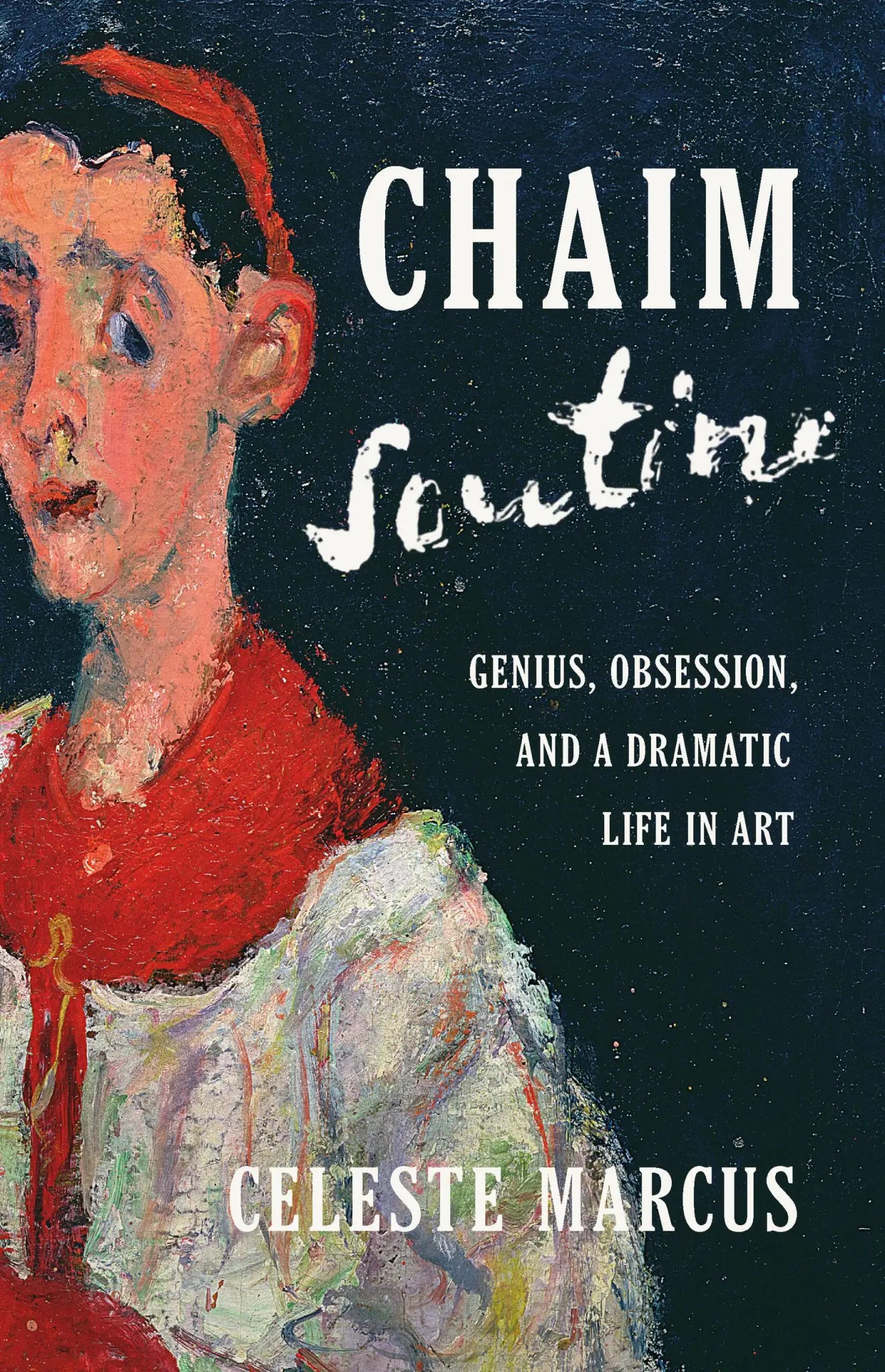

After literal years of research and work, my ultra-keen Liberties editor (and, yes, friend) Celeste Marcus has published her biography of Chaim Soutine, which you can buy here and at all quality booksellers.

Viva Zohran. Viva New York City. Til next time xxx

still need to get around to listening to Icons. Wasn’t really aware of her prior to (& subsequently falling in love with) All Thoughts Fly when it dropped.